Rethinking Who Creates, Shares, and Sustains Local News: Why Information Stewardship Is the Future

The local news field is redefining itself in the midst of a polycrisis. And that's exactly why we wrote our latest report.

At Commoner Co, we've spent years working in newsrooms, with support organizations, and alongside funders who are all grappling with the same fundamental question: How might we reimagine and rebuild a local media ecosystem over the next decade that serves communities—and who is working toward that future?

Our new report, "This is Local News Now: Rethinking who creates, shares, and sustains it," commissioned by Press Forward, tackles this head-on by proposing a radically expanded definition of who informs our communities—and why that matters for the future of civic life in communities across the U.S.

The Core Thesis: It's Time to Embrace Information Stewards

For too long, we've organized local news around business models and tax statuses rather than around the communities these outlets serve. But here's what we've learned: The flow of local information has always moved between various actors and institutions and outside of the purview of professional journalism.

That's why we're beginning with the concept of information stewards—anyone who is intentionally contributing to meeting a community's information needs by making and distributing news and information. This includes:

Local news providers (journalists and newsrooms)

Civic promoters (government agencies, libraries, nonprofits, schools)

Community catalysts (engaged residents, neighborhood organizers, local advocates)

We undertook this work because the dominant ways of understanding local news types—organized by operating structure rather than community purpose—prevents the field from making effective investments to ensure communities' information needs are met.

A shared identity is essential to any field of practice. It helps create shared narratives to attract support, build unity against external threats, and work smarter. The local news field needs this clarity now more than ever.

Three Takeaways From The Authors

1. Public Policy Has Shaped Who We Consider "Real" News—And It's Time for an Update

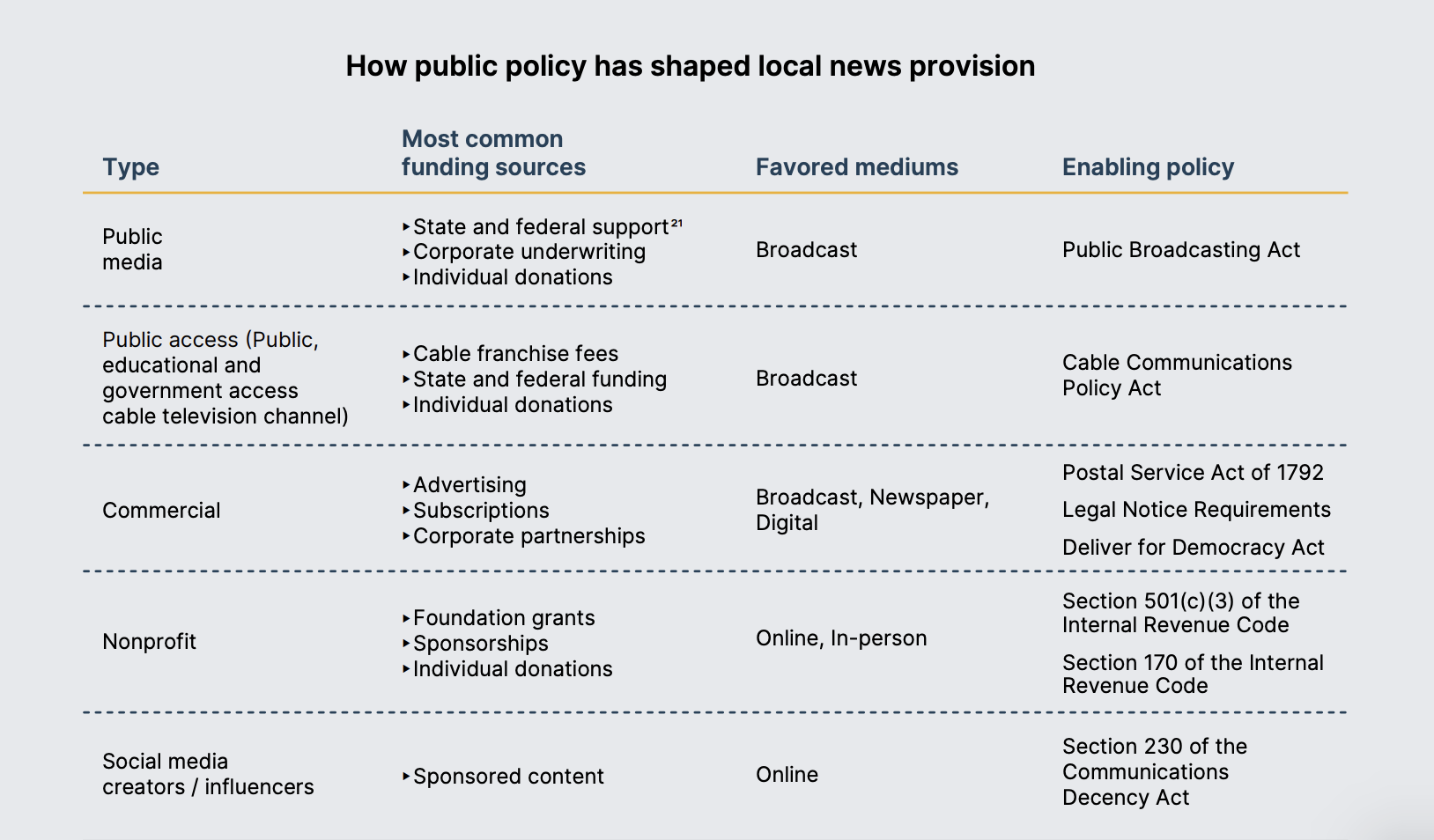

Public policy wins (and losses) have profoundly influenced what we consider legitimate local news. The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 created public media. The Cable Communications Policy Act enabled public access TV. The Postal Service Act supported newspaper distribution. Each policy created dedicated funding streams and preferred mediums.

But here's the problem: Few of today's policies actually address how local news providers serve community information needs.

We need policies that center communities first, not revenue models, distribution types or operating structures. This means identifying local information gaps and considering how all information stewards—not just traditional newsrooms—can fill them. Organizations like the New Jersey Civic Information Consortium, which enables flexible, community-driven funding, point toward this future, and just this week, we’re seeing California debate whether its recent legislation will evolve toward this model.

2. Community Media Centers Are Essential Civic Hubs

Some of the most innovative work happening in local news isn't happening in traditional newsrooms—it's happening in spaces that combine journalism with public education and civic engagement.

Take CivicLex in Lexington, Kentucky. They host workshops where government employees and residents learn together about city budgets and affordable housing. The city was so impressed they brought CivicLex on to design community feedback processes for Lexington’s strategic plan.

Or take City Bureau’s Documenters network—now in 22 cities—which trains community members to document public meetings and share findings with newsrooms that lack capacity to attend. This isn't just journalism—it's participatory civic infrastructure.

Finally, consider CreaTV in San Jose and the hundreds of other public access stations serving as community media centers across the country. These outlets are rooted in prosocial public policy and have a long history of deep investment, embeddedness and participatory approaches in local communities.

As public media funding becomes increasingly uncertain following President Trump’s dismantling of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, we see bright spots in both emergent and longstanding approaches to creating a media ecosystem that is truly public. These "civic hub" models represent a new type of local news provider that equips residents with skills, information, and resources to participate in civic life. They're not replacing traditional journalism; they're expanding what local news can be. As Sophie van Oostvoorn says in this International News Media Association piece, “This isn’t about abandoning journalistic values. It’s about rethinking how we embody them in a changing ecosystem.”

3. Dealing with Bad Actors Requires an Ecosystem Approach

We can't discuss the future of local information without addressing misinformation and bad actors. But the solution isn't more gatekeeping—it's building stronger ecosystems.

Consider what happened in Oakdale, California, where a popular Facebook group became a vector for false information that led to militia members showing up to defend against a nonexistent threat. The group's founder eventually enlisted other residents to help with fact-checking, but by then, frustrated members had splintered into new groups.

The opportunity lies in ecosystem approaches that leverage trustworthy information sharing. Rather than competing, the local weekly newspaper and community Facebook groups could coordinate to strengthen how reliable information flows throughout the community. When information stewards understand their distinct roles and work together, they can collectively raise information standards.

Bright spots we’re seeing in the field

In addition to the case studies we cite in the report, we’re seeing even more recent bright spots in the local news field that reinforce many of our report’s recommendations.

The Local News Impact Consortium is studying information ecosystems, which they define as the study of how news and information flows through communities. They’re advocating for more standardized data when it comes to studying ecosystems because we can track change over time, comparisons to other communities, and not having to reinvent the wheel every time we ask similar questions. To that end, they’ve been working on a Newsroom Census toolkit that offers some standardization of terms and research methods when it comes to building databases of who qualifies as part of a community’s local news and information ecosystem.

We also applaud Pittsburgh’s Public Source for mapping its local “creators and trusted messengers,” because it recognizes it needs to expand “its audience reach and deepen engagement within communities” who aren’t as aware of Public Source’s work.

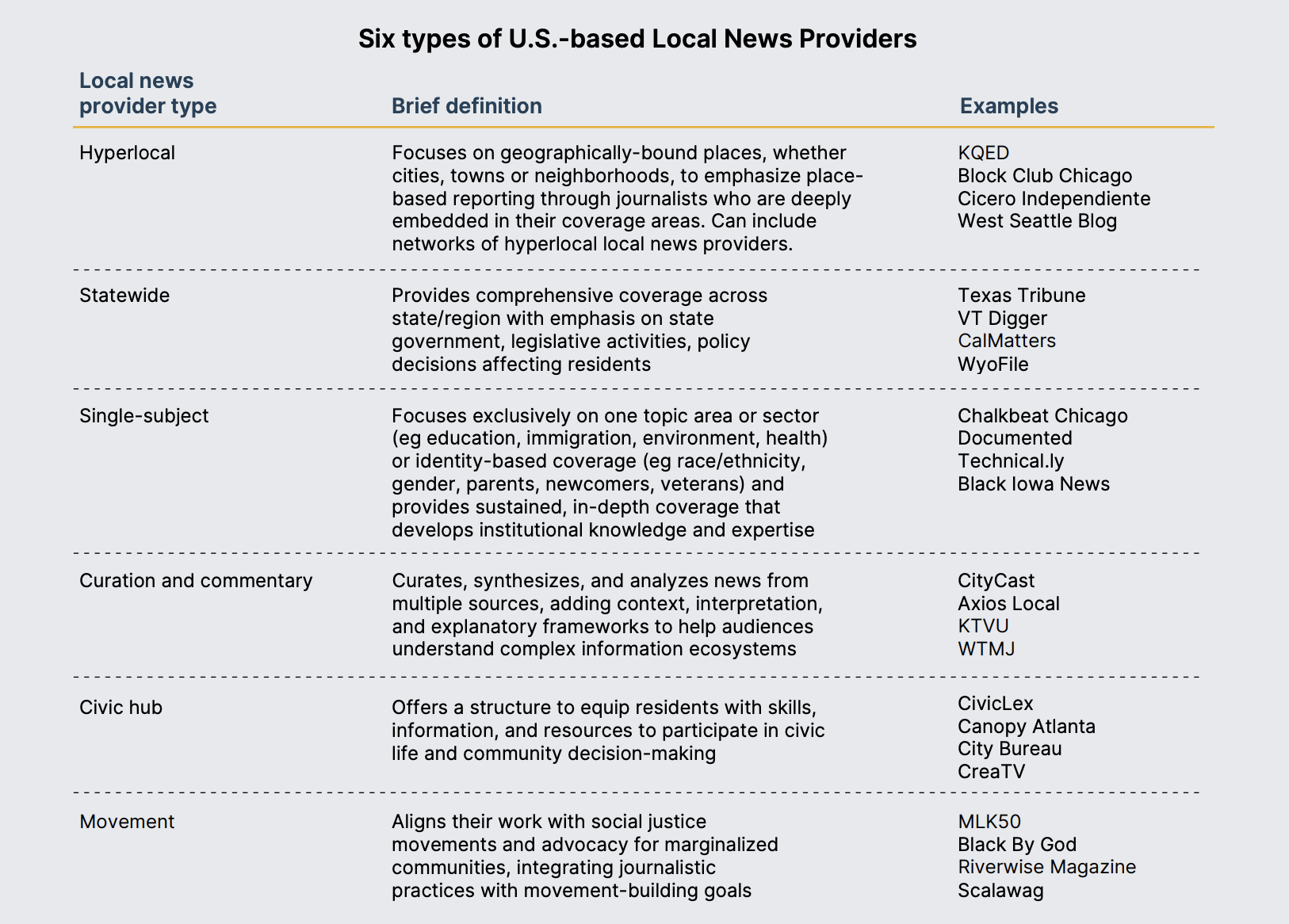

The Latino Media Consortium, which launched last year to support Latino-serving digital media publishers, wrote about how they’re adopting the framework we share in a number of ways. One example is when they intake members into their network, they ask the local news provider to “identify the primary role in which they reach their audiences” using the six types of local news providers from our report, because “that lens helps neighboring publishers align instead of overlap.”

Finally, the newly launched News Creator Corps, led by long-time media critic Jay Rosen, is running an eight-week program for “creators who have established themselves as trusted leaders on one or more platforms, including, but not limited to, Instagram, TikTok, Twitch, Substack or YouTube.” The goal? “ By investing in these information sharers through training, partnerships, and community building, we can make social platforms safer for all.”

All of these examples speak to the core thesis behind the definition of information stewards: If we want to make sure all communities’ information needs are being met, we have to recognize and support an ecosystem approach. Journalists are a core part of that approach, but not the only part.

The Path Forward: From Competition to Coordination

We're not arguing that verification standards don't matter or that all information should be equally trusted regardless of the source. Instead, we're saying that understanding the motivation and professional affiliation of different information stewards helps communities make better decisions about what information to trust.

Our first report in this series explored the role—including the wins and challenges—of journalism support organizations, and found a similar path forward: the future of local news isn't just professional—it's participatory. By broadening who we consider part of the solution, we can build more resilient, representative, and effective information ecosystems.

Because here's the bottom line: communities need information stewards, not just information gatekeepers.

Ready to dig deeper? Download the full report and join the conversation about reimagining local news for the communities we serve.

Commoner Company is making civic life more accessible and inspired. Our work brings mission-driven organizations, philanthropies and communities to the table to make ambitious ideas actionable. Learn more about our work here or get in touch to see how we can work together.